Why is there so much confusion around the term giclée? That was one of the questions Kim Hall asked me to cover in the article on “The State of the Art of Art Reproduction” that I wrote for the July/August issue of Professional Artist magazine.

Why is there so much confusion around the term giclée? That was one of the questions Kim Hall asked me to cover in the article on “The State of the Art of Art Reproduction” that I wrote for the July/August issue of Professional Artist magazine.

For the main body of the article, I interviewed a number of experienced fine-art printing experts. They helped me explain how and why different types of printing methods have evolved and are currently used for art reproduction. Printing methods include: lithography; serigraphy; electrographic digital presses; and aqueous, solvent and latex inkjet printers and inkjet printers that use UV-curable inks).

After explaining how printing technology has evolved, I decided to address the “giclée” question in a sidebar. I thought about the many different ways the term has been used since I first started writing about digitally printed fine art in the mid-1990s.

Most often I have seen the term used for art reproductions made with pigment inks on aqueous inkjet printers. But I have also seen the term “giclée” used with digitally printed photographs as well as art prints output on solvent or latex inkjet printers. Prints made on color copiers or with fast-fading dye inks have also been called giclées. The lack of a print-technology-specific definition for giclée has made it difficult for gallery owners and museum curators to establish their value.

For the article, I asked the printmaker who coined the term “giclée” to share his thoughts on why there’s so much confusion. Jack Duganne, of Duganne Atelier in Santa Monica, California, said his original intent “was that a print could be called a ‘giclée’ if the person who created it (or contracted to have it printed) would be using it as a fine artwork—a print that would be signed by the artist.” Although the term later became associated with inkjet printing, he believed the term would be used for many forms of digital output. Today, the definition of giclée seems to change to suit the needs of whoever is selling giclées—regardless of whether the prints are signed or not.

To avoid confusion, some artists and printmakers are moving away from the term “giclée” and being more specific in describing what printing technology was used to make the print.

While writing the article, it occurred to me that the term “giclée” isn’t the only word being redefined as technology continues to evolve. Even in the era of sharing photos on Facebook, some online sources still define a “photograph” as an “an image, especially a positive print, recorded by a camera and reproduced on a phototosensitve surface.” The rapid adoption of digital publishing technology and e-readers is also likely to change to how we define books and magazines. We’re already starting to use more specific terms such as “photo prints” or “printed books” or “printed magazines.”

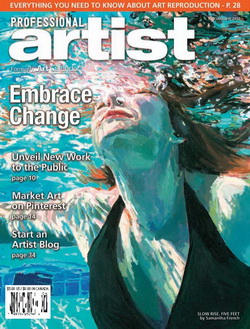

Other Articles in the July/August issue

The July/August issue of Professional Artist contains a wealth of articles designed to help artists adapt to ongoing changes in how art is produced and marketed. Some of the marketing-related articles in this issue include:

The July/August issue of Professional Artist contains a wealth of articles designed to help artists adapt to ongoing changes in how art is produced and marketed. Some of the marketing-related articles in this issue include:

- Blogging for Artists by Terry Sullivan

- Using Pinterest to Promote Your Work by Katie Reyes

- Is Email Marketing Effective? by Daniel Grant

- Best Business Practices: Introducing New and Different Work to the Public by Jodi Walsh

- 22 Golden Rules for Saving Time by Renee Phillips, the Artrepreneur Coach

Other articles in the issue talk about embracing change, working with art galleries, weathering painful criticism, introducing new and different work to the public, using CFL lighting systems to photograph artwork, and using ArtBooks data to make business decisions. The cover art “Slow Rise, Five Feet” shows a painting of an underwater scene by Samantha French.

You can buy single copies at many Barnes & Noble stores, download a digital version of the current issue for $3.95, or subscribe for $37/year in the U.S.

LINKS

Professional Artist Magazine: July/August 2012 Issue

Professional Artist Magazine: The State of the Art of Art Reproduction